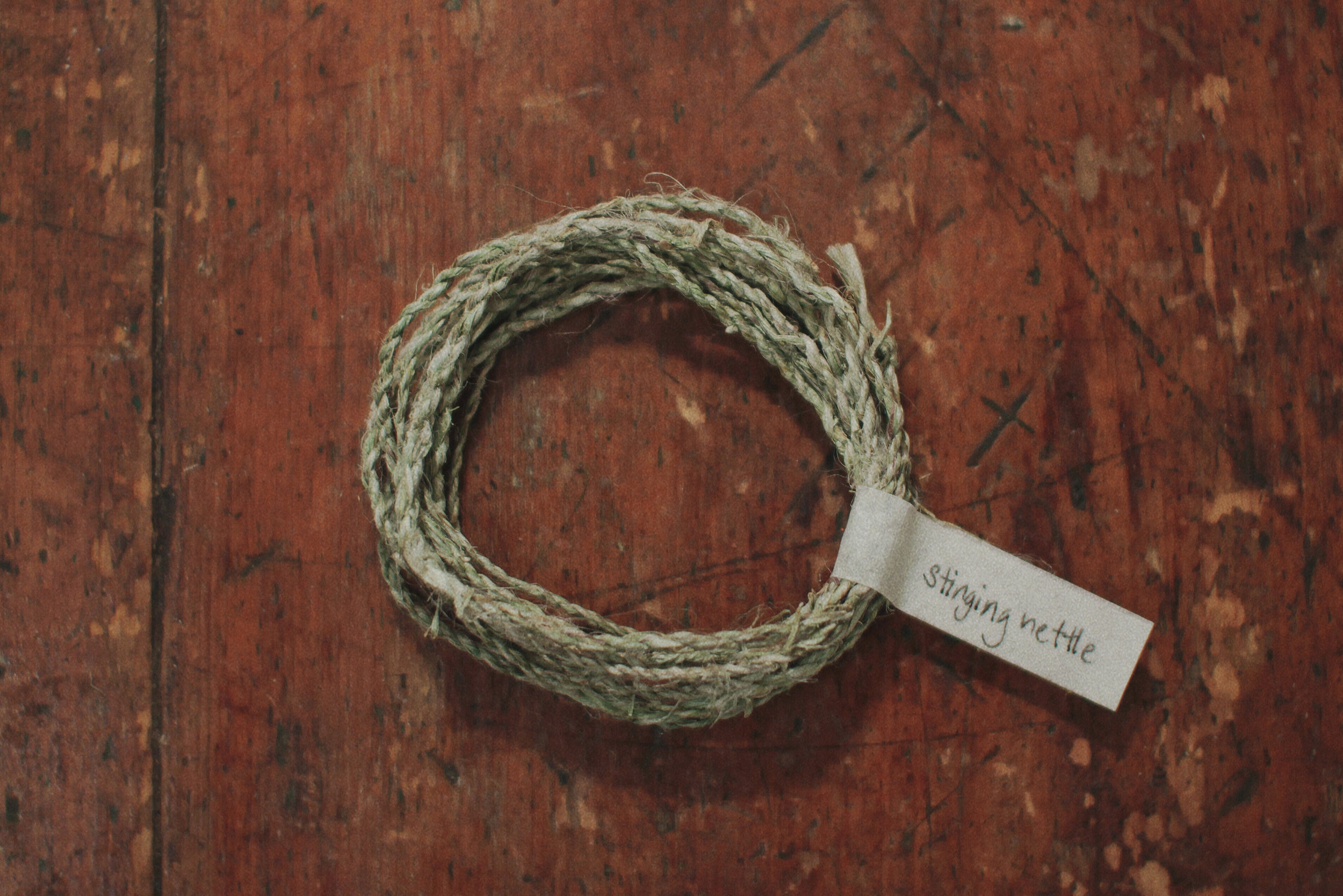

STINGING NETTLE CORDAGE

As a therapist I am acutely aware of the high cost of therapy, which can make it inaccessible to many people. For this reason I am very passionate about empowering people with the skills and tools to support their own mental health.

The act of doing a simple and mindful activity that engages our senses has been shown to have a meditative and integrative effect on the brain and nervous system. Recently, we have seen colouring books for mindfulness, knitting for anxiety and other 'mindless' mindful skills regain popularity. These skills help to integrate the hemispheres of the brain and have a soothing, rejuvenating effect, which is helpful in targeting anxiety and depression.

As a child, I suffered from chronic illness. Often all that I could do was lie on the couch and watch TV. I was unable to read due to my eyesight and often barely able move. At times, this led to a deep sense of sadnes and a feeling that I had no purpose or value in life, and my only role was to take up space.

Years ago, a good friend taught me how to make cordage from natural materials. I soon experienced firsthand the effect of working on something very simple, watching something take shape from nothing before my eyes. It aided in providing a distraction and it gave me a sense of accomplishment, a surprising feeling of purpose and a sense of self-worth.

One of the beautiful things about using natural materials is that they can be found for free in nature. I have seen time and again, both for myself and for others, how empowering it can be to learn to identify and use materials in our immediate environment, and how it instills a sense of confidence and agency. Practicing mindful skills that occupy the hands and other senses can also provide an alternative for people who would like to enjoy the benefits of a meditation practice but struggle with traditional (eyes closed, sitting on a cushion) meditation.

During those times when I was so sick, I would still sit, or lie-down to be more accurate, and maybe watch TV, but I worked on making cordage while I did so. This completely changed the experience for me, and became an important life lesson. On days when you are overwhelmed by health or feeling useless and unproductive, try to accomplish one thing - just one thing, however small that thing may be. The mental and emotional effects of something so simple can be incredibly powerful.

This week, we made cordage using the stalks of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica). The time to harvest stinging nettle for cordage is toward the end of the summer or early autumn when the leaves are beginning to wilt but the plants are still alive. You will need a good bundle of nettle as each individual stem only produces a small amount of fibre. The first step to preparing nettle for cordage is to strip the stems of their leaves by running your hand from the bottom of the stalk to the top in one smooth motion. I know some people who do this with their bare hands - the little stingers point upwards, so it is possible to strip the stalk without getting stung - but you might want to wear gloves for this part.

Stinging nettle fibre comes from the outer layer of the stem, so the next step is to separate these fibres from the woody pith at the centre of the stem.

In order to do this, we need to split the stem open. Using a rock or a hammer, I like to pound the entire length of the stem, flattening it. It will naturally begin to split and you can insert your finger, splitting the entire length of the stem. You will notice in this photo that the stem is hollow. When split open and laid flat, there are two layers: the inner woody part, and the outer fibrous bark. The outer bark is the part we want to keep.

Once the stem is split open, you can snap it in half - the woody pith will break, while the fibres (outer layer) will remain intact.

Gently peel the fibres away, separating them from the pith.

This is what the fresh separated fibres look like. Allow them to dry overnight.

Before beginning to form the cordage, I like to roll the fibres vigorously between my hands or on my jeans, allowing any additional woody materials to fall away. If you skip this step, the cordage tends to be more rough and brittle. After doing this, what should remain is a beautiful flaxen fibrous material.

Now that your fibres are prepared, it is time for the reverse twist. This is a simple method which forces two individual strands of fibres to twist around each other, creating a strong piece of cordage.

The first step to the reverse twist is to begin by twisting a single strand of fibres until they naturally start to fold in on each other and create a small loop.

From here on out, there are two actions - first: twist the top fibres together away from you, second: bring the top strand back toward you. Repeat. (Watch the video below to get a better idea). Keep adding fibres as you go.

Once your fingers get the hang of it, you will be able to perform this action quickly. Very soon, the nettle cordage will take shape before your eyes!